Download file | Play in new window | |

They say no news is good news, but that isn’t always true.

When it comes to dementia, we very much want there to be news. We’ve spent the last 25–30 years searching for a cure — or even a treatment — but it continues to elude us.

In a previous post, we shared an update about the state of affairs surrounding dementia research, especially the stagnation in breakthroughs for treatment. We focused on Alzheimer’s disease — the most common type of dementia — and we’re coming back to discuss updates on that topic and for 2023.

When it comes to a cure, the sad truth really is, there is no update. But we still have plenty to talk about — and there is hope.

Certain tools, such as APOE genotype testing, can inform you about your risk for developing Alzheimer’s so you can take offensive measures. Some evidence even suggests Alzheimer’s may have a metabolic basis, which would give you more weapons to wield. We can also anticipate breakthroughs in diagnostic screening and risk stratification.

While we can’t treat Alzheimer’s at this time, if we can identify it early, we might be able to slow it down long enough to see a medical breakthrough on a therapeutic level. For now, our goal is to arm you with information so you and your doctor can manage your risk factors.

Dementia Is Not a Single Disease

For many people, the term “dementia” is synonymous with Alzheimer’s. But dementia isn’t one specific disease. It’s an umbrella term for a group of diseases that rob people of their memory, cognition, and eventually their lives.

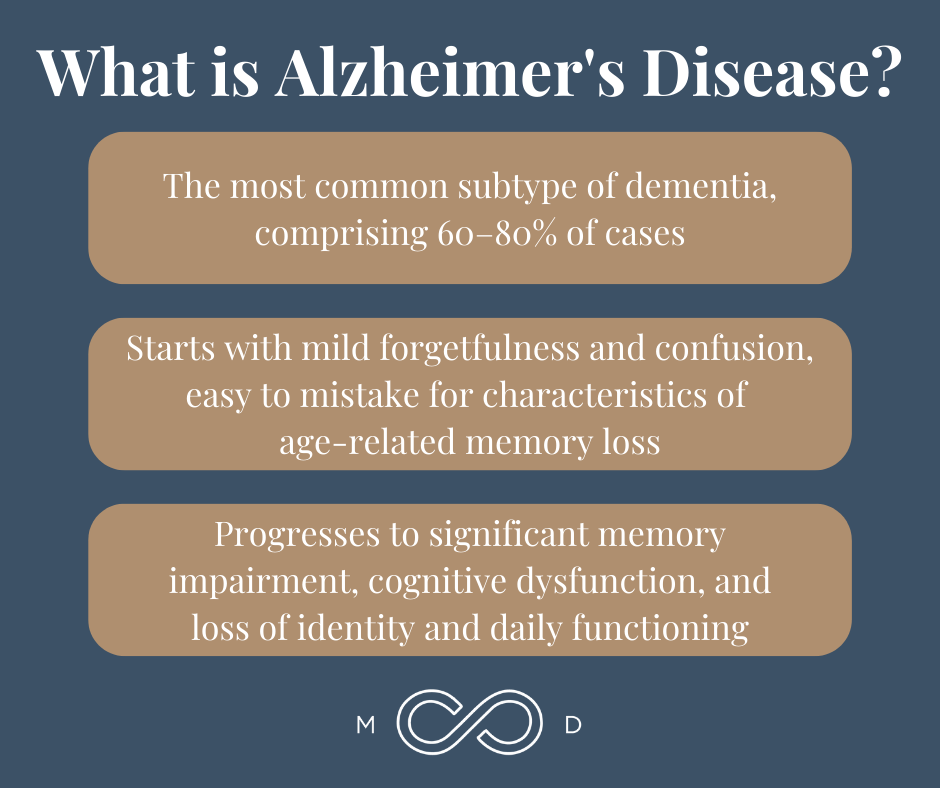

Alzheimer’s dementia is by far the most common subtype of dementia, comprising 60–80% of cases. It starts with mild forgetfulness and confusion, easy to mistake for characteristics of age-related memory loss. It then progresses to significant memory impairment, cognitive dysfunction, and loss of identity and daily functioning.

Vascular dementia occurs next most often among dementia types, comprising 10–20% of cases. It results from reduced blood flow to the brain, usually from a stroke or a series of mini-strokes (transient ischemic attacks, or TIAs). Vascular dementia does lead to memory loss, but problems with thinking and problem-solving tend to be more pronounced.

Lewy Body dementia, which includes Parkinson’s disease, is the third most common type. It results from a buildup of abnormal proteins, or Lewy bodies, in nerve cells in the brain. This type of dementia causes confusion, trembling, stiffness, movement and balance problems, and hallucinations.

Because of its prevalence and/or people’s personal experience with the disease, Alzheimer’s dementia is the most well-known type, and the one that tends to elicit the most fear. Equally fear-inducing — and maddening — is that the past 25–30 years of research have brought little advancement in Alzheimer’s prediction and treatment.

Untangling the Toll of Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease is the seventh-leading cause of death in the U.S., killing nearly 120,000 people per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control. There are instances of early onset, but it generally strikes after age 65.

Unlike other top killers, the lack of treatment options makes Alzheimer’s uniquely complex and stressful. Drugs like Aricept (donepezil) can slow disease progression, but there are zero options for reversal or prevention. And we don’t have the diagnostic capabilities to detect Alzheimer’s like we do for chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes. There may be a few subtle signs, but by and large, Alzheimer’s hits without warning.

It’s a disease that doesn’t seem to discriminate. We can’t definitively say, for example, that women get Alzheimer’s more than men. This uncertainty contributes to the fear.

I don’t like to see people suffer, period. But Alzheimer’s brings a unique kind of suffering in that family members have to watch their loved one’s identity get stripped away. In the early stages of the disease, the patient bears the brunt of the suffering as they grapple with memory loss and the accompanying anxiety and distress. Later, family and caregivers have the gut-wrenching experience of witnessing the erosion of the patient’s independence and identity.

Alzheimer’s brings a specific kind of pain and suffering that I don’t find in any other disease process. Losing the ability to know who you are is uniquely painful for family members, who are very aware of what has been lost.

As a society, we’ve collectively lost years of Alzheimer’s progress because we were chasing the presumed cause: protein-based plaques and tangles in the brain. We thought that if we could prevent them from forming, we could prevent Alzheimer’s from developing. Now it appears that these plaques and tangles are more of a downstream symptom, and that preventing them doesn’t prevent Alzheimer’s.

Yet this has been our focus for 25 years. To me, the resulting lack of progress is the single greatest failure in all of medicine to date.

However, it’s fair to say we’re making advancements in early detection. Things like imaging, neurological testing, and cognitive decline screening provide earlier evidence of signs of Alzheimer’s. But this hasn’t changed the outcome. We’re missing something very significant that’s keeping us from developing a curative treatment.

Here’s an analogy I like to use: We’re good at identifying, diagnosing, and treating pneumonia. But let’s pretend antibiotics didn’t exist. Are early detection and diagnosis useful if there’s no treatment? Would you want to become aware of something that will ultimately kill you if you can’t do anything about it? Or would you rather not know?

Neither option seems satisfying to me.

Know Your Modifiable Risk Factors

When it comes to risk stratification for any disease, we look at modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. We put them into two buckets, and from there we manage what we can manage, and change what we can change.

The single greatest non-modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s is age. You can’t prevent aging, and the longer you live, the greater your chances of developing a chronic condition. Age is the number one driver of chronic disease, period.

Family history is another risk factor; you’re at greater risk if you have a parent or sibling who developed Alzheimer’s. Evidence also suggests Alzheimer’s risk is highest for African American and Hispanic populations. But so far, we haven’t known much about modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s.

We can potentially identify high-risk people and diagnose them early if and when the disease process starts. Our best effort from there is to add some Aricept to slow progression. But there’s nothing in our arsenal that can reverse, cure, or prevent Alzheimer’s.

Here’s where it gets interesting, though. A growing body of evidence suggests Alzheimer’s may be a type 3 diabetes — specifically, insulin resistance at the brain level.

That’s not settled science, but it’s compelling, intriguing, and plausible. If this is the case, then the modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s should be the same modifiable risk factors we talk about for cardiovascular disease. These include:

- Smoking

- High blood pressure

- Elevated cholesterol

- Diabetes

- Obesity

We already know managing these risks protects you against vascular dementia. When it comes down to it, what’s good for the heart is good for the brain. You don’t want to smoke, and you want to keep your blood pressure and blood sugar under control.

You do this through diet and exercise — the things medical experts beat the drum about. You hear it from us over and over, because we know these things work.

Addressing these risk factors will, at minimum, help you modify your risk for vascular dementia. If we have some good fortune and prove there’s an insulin resistance component to Alzheimer’s dementia, these same efforts will also help us with risk stratifying for that disease.

This is where I see hope.

APOE Genotyping Helps Predict Alzheimer’s Risk

There’s a lot we don’t know about Alzheimer’s disease, but there seems to be a clear genetic, familial component. When the disease appears in subsequent generations, it tends to happen a little earlier and a little more aggressively each time. So, a thorough family history allows us as physicians to watch for a potential unique risk.

The APOE e4 genotype is probably the most well known, significant scientific risk factor linked to generational Alzheimer’s. APOE stands for apolipoprotein E, and it’s related to how your body processes lipids.

You inherit two APOE alleles, one from each parent. There are six possible combinations a person can have: 2/2, 2/3, 2/4, 3/3, 3/4, and 4/4. Having one or two copies of APOE e4 is associated with a higher risk of Alzheimer’s, and in some cases, an earlier onset. APOE e3 is thought to have a neutral effect on Alzheimer’s risk, whereas APOE e2 may offer some protection.

As with other genetic risk factors, it’s important to note that even two copies of APOE e4 does not mean you are destined to develop the disease.

Because I love a good analogy, I invite you to look at it this way: I have fair skin, freckles, and northern European roots. I don’t need genotyping to know this; my phenotype, or my observable characteristics, lets you know I’m at a higher risk of developing melanoma. But there are things I can do — wear sunscreen, put on a hat and sunglasses, and minimize my sun exposure during peak hours — to lessen the chances I’ll get it. My genes are not my destiny.

It’s the same with Alzheimer’s. What you do from a modifiable-risk-factor perspective can turn these genes on or off. Two copies of APOE e4 isn’t destiny — but you need to stay on the offensive.

To help inform you about your risk for developing Alzheimer’s, we’ve added APOE genotyping to our new member blood panels at Brentwood MD.

Self-Advocacy Is Key to Staving Off Chronic Illness

When it comes to Alzheimer’s disease, there are multiple areas of potential breakthrough, and I’m hopeful new findings are on the horizon. We don’t have a lot to report now, which makes this a difficult conversation — but it’s an honest conversation, which I’m thankful for. All progress begins with telling the truth.

The good news: You have the power to take control of your health care. It starts with learning how to be proactive and persistent about your goals.

First, find a team of providers who align with your values and goals. Your doctor’s office should be a safe space where you feel heard and respected. Getting a diagnosis or having an unexpected change in your health can be frightening, so don’t wait until you’re sick to find a team of providers you love.

When you have that team, remember that you have not only the power but the obligation to direct it. Even in a concierge medicine model, doctors are busy. It’s important that you do your research, educate yourself, and voice your questions and concerns. Don’t be afraid to ask, “Am I doing all I can to protect myself against cancer, diabetes, heart disease — and dementia?”

Keep your eyes open to what’s important to you. That diligence, combined with the right team, really sets you up for the best odds of avoiding a proverbial iceberg. But if you do find yourself up against one, you’ll be able to navigate it in an elegant way for the best possible outcome.

At Brentwood MD, we provide high-touch, ultra-personalized care. We now include genotype testing as part of our new-member bloodwork. Click here to learn more about our member services.

Dr. Aaron Wenzel is a concierge physician specializing in the care of fast-moving entrepreneurs, executives, and public figures in the Nashville, TN area. Dr. Wenzel’s diverse life experience and extensive training in family medicine, emergency care, nutrition, and hormone replacement therapies give him the unique platform to provide unmatched care for his patients.